Mimi Oliver ’22 was a little nervous a few weeks ago, thinking about going caving with her Geographic Information Systems class. On Aug. 17, she and her classmates would hike to a cave in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains and then spend the day inside taking measurements, collecting data, and exploring.

“I was kind of scared,” Oliver, a transfer student and environmental science major from Springfield, Virginia, said. “I don’t really like tight spaces, so when I think of caving I think we’re going to be crawling around, slithering through different passages. I was a little nervous, but also excited because it was something I’d never done before.”

Once inside the cave, which sits on private property about 45 minutes from the University of Lynchburg, Oliver’s jitters vanished. “I thought it was just amazing,” she said. “After that long hike up the hill, it was beautiful to see what we were going to do.”

What Oliver and her classmates are doing over the course of the fall semester is creating a map of the cave, something that’s never been done by a class at Lynchburg. The idea originated at a faculty workshop this past summer where Tim Slusser, Lynchburg’s director of Outdoor Leadership Programs, was giving a talk about integrating outdoor programs into academics.

Afterward, Dr. Dave Perault, who has been teaching GIS at Lynchburg for 20 years, approached Slusser about a collaboration. “I wanted to get my class outside and away from computers,” Perault said. “Tim mentioned caving, I mentioned how GIS is all about mapping, and we eventually ended up with the idea for a cave-mapping expedition.”

Perault, a professor of environmental science and biology, said he always looks for ways to get his students outside. “Since we spend so much time computer mapping, the opportunity to physically map a feature, such as a cave, is one I could not pass up,” he said.

“This should help students gain a true appreciation for the science underlying mapping and what goes into making the maps we use daily.”

Before the trip, the GIS class met with Slusser and members of the James River Grotto, a local caving group, for training on caving and mapping. “[They] taught mapping techniques, reviewed safety protocols, and explained what to expect and pack,” Perault said. “This saved time on the day of the expedition and helped put us at ease.”

A week later, the class — accompanied by OLP staff and two Grotto members — put the training to good use. “Most of us were both excited and a bit apprehensive, especially at the mouth of the cave, simply wondering what to expect,” Perault said. “Tim and the others quickly put us at ease with their knowledge and safety protocols.

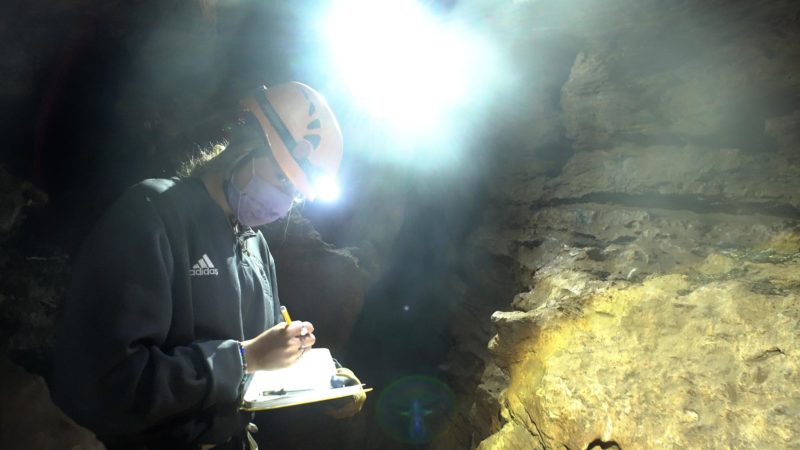

“Since we started mapping immediately, our minds quickly switched gears to work mode. … I noticed students giggling with fear and others giggling with excitement, but both groups cinched down their helmets and went to work.”

The cave, which had only recently been discovered, was larger than the group anticipated and had two main caverns. “The first was very large, with plenty of room to stand and move around,” Perault said. “It had ceilings over 20 feet high in places but also places where you had to crawl. The second cavern was very small and required tight squeezing to access.”

Oliver, on her first caving expedition, stuck to the more open spaces. “We went through the entrance and it just opened up. There was a little bat on the ceiling, which I loved,” she said.

“I love bats, so getting to see one in its natural habitat was really cool. All the different rock formations and outcroppings. It was really awesome to see in person and it was great that it wasn’t a tiny little crawl space for the most part.”

Brennan Straits ’22 and his group ventured into some of the cave’s tighter spots, including an 18-foot-long, pipe-like passage that opened up into a bigger room. “Getting down to that room was pretty tough,” the international relations major from Middletown, Maryland, said. “You had to go legs first and crawl in, and once you got into the room it just opened up.”

Using a variety of tools, Oliver, Straits, and the other students — about a dozen total — mapped portions of the cave. “The class successfully mapped the beginnings of both caverns,” Perault said. “Using tape measures, compasses, clinometers, and lasers, the azimuths — or directions — and inclinations — or elevation changes — were measured at waypoints along each cavern.

“The size of the cavern at each waypoint was also measured, and features were described and added to the map. Neither cave was fully mapped, so next year’s GIS class gets to return and continue the work.”

Oliver said the experience gave her a greater appreciation for people who map caves on a regular basis. “Having that experience with non-digital instruments, to actually do that mapping, gave me a big appreciation for people who have been doing that for a really long time,” she said.

“We had the field day before we went out, to get the hang of how [the instruments] worked, but it was really amazing how, once we got in the cave, it was a completely different experience using them. It was a good experience.”

Straits agreed. “It was a good introduction to the class, that’s for sure,” he said. “An awesome start to the first two weeks. … We’re going to be spending a lot more time in the computer lab, working software and our GIS systems, plotting maps, but it was interesting to just get out of the classroom.

“A lot of us are experiential learners and getting outside and working with stuff that’s hands-on is sometimes the best way to learn. I’m looking forward to … coming to class on Tuesdays and Thursdays, because I know it’s going to be something interesting, something thought-provoking.”

As for Slusser, he’s looking forward to more collaborations with academics. “[It] went really well,” he said. “I’m excited to keep doing it in the future. The students had a good time. It was a great opportunity to expose them to caving and cave exploration survey. It’s a great partnership between us and the academic side. …

“I want to reach across the aisle and keep doing this. The more ways we can reinforce the things they’re doing in the classroom outside the classroom and vice versa, the better. OLP is creating space for lifelong recreation and getting folks outside. We’re big proponents of experiential learning.”