Alexa Watkin ’23 carefully opens one of the burial books in the office of Presbyterian Cemetery, a historic graveyard that’s located about three miles from the University of Lynchburg. She thumbs through the pages that list the names of Lynchburg-area residents who have been buried at the cemetery since it opened in 1823.

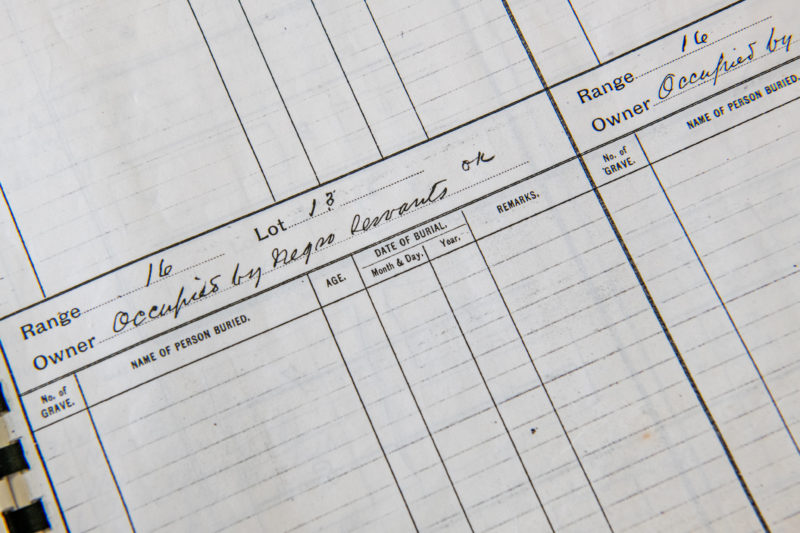

She stops at a page that’s largely blank. It’s divided into six sections — six plots — but the only thing written at the top of each section is “Occupied by negro servants.”

There are no dates indicating when the plots were purchased, or by whom, or when burials were made there. There’s also no indication as to whether the African-American servants were free or enslaved people. Watkin said she consulted with staff at the Lynchburg Museum, where she’s doing an internship, who could only narrow it down to most probably the 19th century.

At the actual gravesite — an unmarked, grassy rectangle in the cemetery’s oldest section — there are no markers, only large, barely perceptible indentations in the ground. Recent testing determined that the soil had been disturbed there and, when compared with known graves surrounding the section, it was consistent with a burial ground.

According to the burial book, there is space in the section for perhaps a couple dozen burials, but identifying the individuals buried there will be difficult, if not impossible. “It will be a stretch to find any actual evidence of who’s buried there,” Watkin, a history major with minors in museum studies and German, said.

“The carelessness kind of shocks me because if you look at how the other people were documented, it’s been done so carefully. [In that section], they didn’t even care to put an ‘X’ that someone was buried there. I’m shocked that it was allowed. It only takes five minutes to write that information there. They didn’t care at all.”

Throughout the academic year, Watkin has been volunteering at the cemetery twice a week as part of the University’s Bonner Leader Program, which emphasizes community service, leadership, and social justice.

Two other Bonners, business management major Schulyer Rowe ’21 and economics major Matthew Varsi ’22, are also volunteering at the cemetery, helping out with office management, grant writing, and marketing and budget issues.

Last fall, Watkin helped load burial information into an online database, but this spring she wanted to work on what cemetery officials are calling the “servants’ section.” She’s currently working with cemetery director Lara Jesser-Abell on a project that will someday memorialize the people buried there.

Watkin taught herself iMovie and made two videos about the project, which have been posted on the cemetery’s Facebook page. She said she and Jesser-Abell also want to collaborate with the Legacy Museum, a local museum devoted to African-American history, and other area stakeholders about the wording of the eventual monument and a dedication service for it.

She hopes that, through the project, she can help right some past wrongs.

“Obviously, you can’t ever make it right, that those people were careless,” Watkin said. “If they were slaves, they weren’t treated well in life or death. It would be important for the community to have them recognized as human beings, like all the other people who were buried here.”