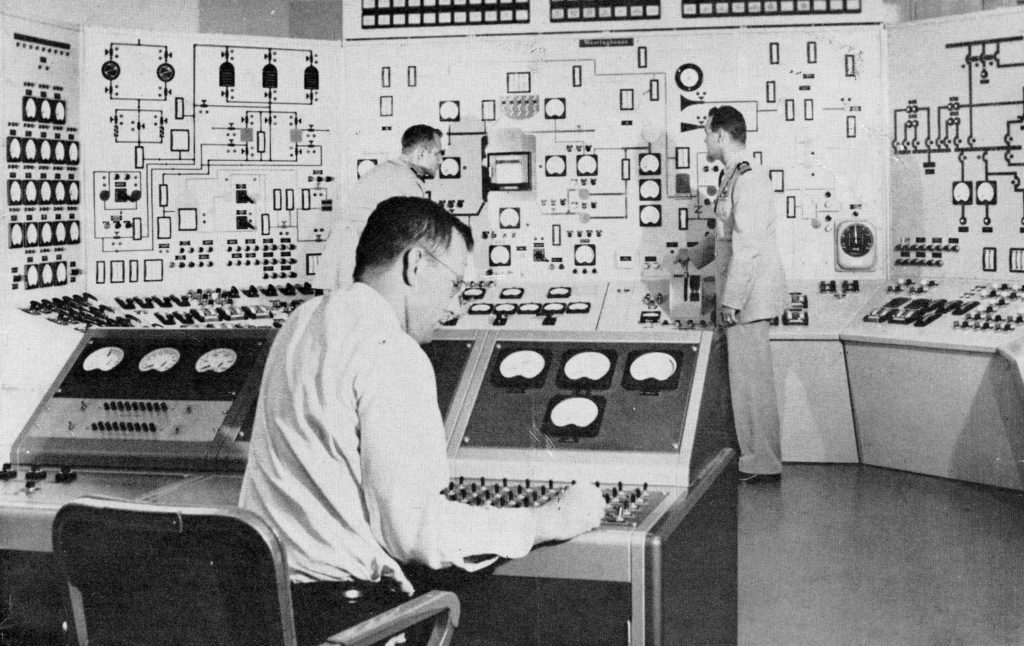

When Hobbs Hall opened 60 years ago, there was a mock nuclear reactor control room in the basement. It was off limits to almost everyone on campus.

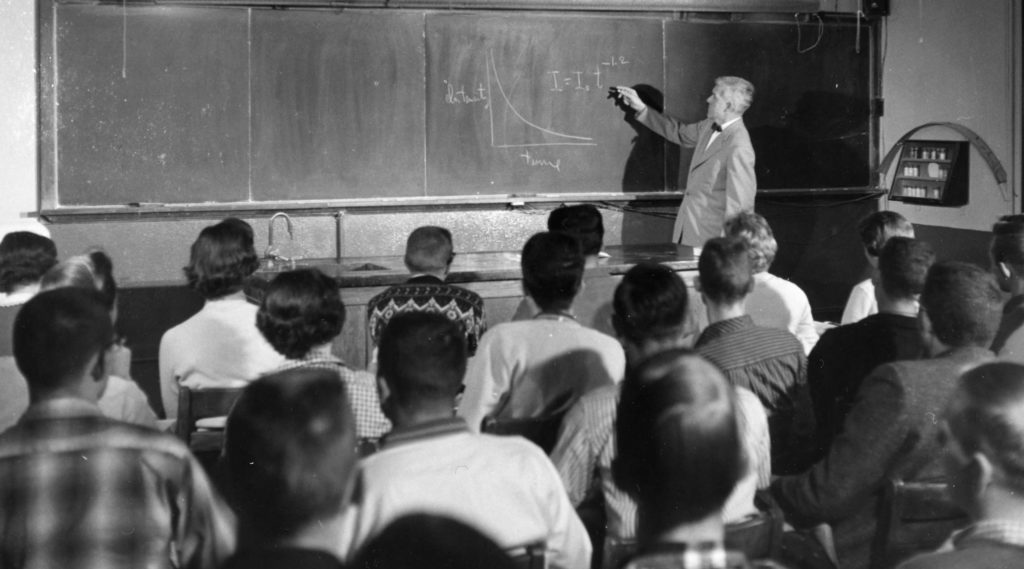

At the time, Dr. Shirley Rosser ’40, a legendary Lynchburg College physics professor, was teaching nuclear physics to a group of sailors who would soon begin driving the NS Savannah, the world’s first nuclear-powered merchant vessel.

Dr. Julius Sigler ’62, then a freshman, recalls meeting the sailors during their breaks. “This was all top-secret, classified territory in 1959 through the end of the training program,” he said, although he does have archival photos picturing parts of the training. “What the control panel did was highly classified. We talked to many of the sailors casually, but they would not talk about the type of training they were getting.”

This morning, a Virginia historical highway marker was unveiled on Main Street in Lynchburg, just in front of the headquarters of BWXT, the company that built the Savannah’s nuclear engine under its former name, Babcock & Wilcox. The Savannah, now a national historic landmark, was an important part of the history of B&W and Lynchburg College, now University of Lynchburg.

Atoms for Peace

The NS Savannah was commissioned in 1956 as part of the United States’ Atoms for Peace initiative. The ship was meant to demonstrate safe, peaceful applications for nuclear power.

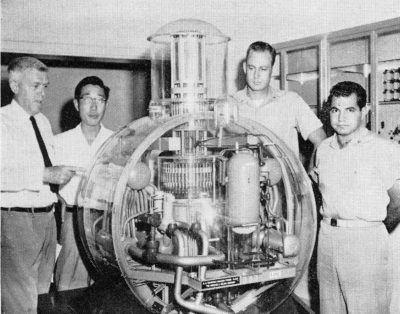

B&W won the contract to design and build the Savannah’s nuclear propulsion system at its Lynchburg-area facilities. Dr. Rosser, who had a consulting relationship with B&W, was the ideal person to train the crew. He could combine his knowledge of nuclear physics with his experience on a Navy ship in World War II, Dr. Sigler said.

“The crew was made up of merchant marine people who had no nuclear experience whatsoever,” Dr. Sigler said. “Dr. Rosser’s role was to teach them elementary nuclear physics. They were talking about how the control room for this nuclear ship would be different from a control room on a conventionally powered ship.”

Dr. Sigler, who went on to become a longtime physics professor at Lynchburg, said the inside of the atom was a hot topic.

“There was a lot of interest in nuclear physics at the time, because it was such a new thing,” he said. “The physics community was learning more and more about the details of the nucleus. There was a lot of optimism about the role that nuclear power would play in the generation of electricity.”

Evolution to University

The Savannah project and the partnership with B&W was a turning point for Lynchburg College. A few years after Dr. Rosser trained the Savannah crew, the College began a master’s degree program in nuclear physics for B&W engineers. Dr. Sigler returned to Lynchburg to teach in that program once he finished his PhD.

Dr. Sigler said the program fit then-President Carey Brewer’s vision for how the College could grow. That vision led to a gradual growth in graduate programs, one of the key parts of the College’s evolution into the University of Lynchburg. “His intent was to create programs that were of service to the local community,” Dr. Sigler said.

Another Rosser family member also had a close connection to the Savannah. Dr. Rosser’s cousin, Ralph Rosser, worked at B&W and assisted with the project. His family was well connected with the College. His wife, Becky Rosser ’47, served as the College’s assistant registrar for some time. Julia Rosser Timmons ’81, the University’s accessibility and disability resources coordinator, is their daughter.

Ralph Rosser became part of the NS Savannah crew in 1963, when the original sailors went on strike for higher wages. He was a nuclear advisor on the ship during several tours, when it would stop at port cities and allow people to get guided tours.

For eight years, the NS Savannah traveled the world, stopping at 45 foreign ports and 32 U.S. ports. More than 1.5 million tourists boarded the ship during its stops.

Today, the NS Savannah is dry docked in the Port of Baltimore, Maryland. Several years ago, Ralph Rosser’s family was allowed to tour the ship and see the place he lived when he was on the crew.

Becky Rosser was glad to hear about the new historical marker. “It brings the story full-circle for me,” she said. “This was a very big part of our lives.”