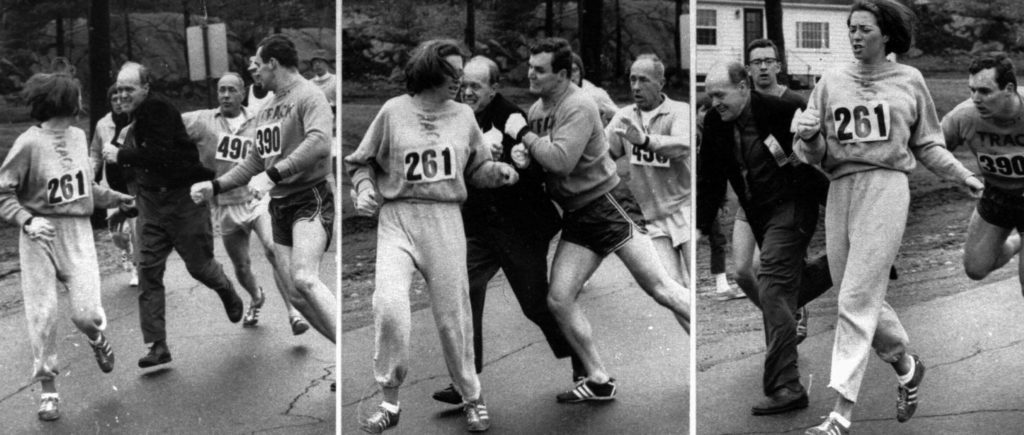

Leather shoes scraped the pavement behind 20-year-old Kathrine Switzer. She turned to see a fierce, angry face just inches from her own. A man in business attire grabbed her shoulders and tried to pull her out of the Boston Marathon.

“Get the hell out of my race, and give me those numbers,” he said, and he tried to swipe the bib with the numbers “261” off her shirt.

Switzer’s heart, already racing, jumped into overdrive. Cameras on a nearby press truck clicked at a feverish pace, capturing her fear as race director Jock Semple kept hold of her until Switzer’s boyfriend charged and knocked the man down.That image is etched into sports history. Switzer was the first woman to run the Boston Marathon as an official entrant. The photos that headlined newspapers around the country the next morning made her an unintentional leader in the women’s sports movement.

It was made possible by a moment with much less fanfare, almost exactly a year earlier, when a Lynchburg College coach asked Switzer to join the track team.

MAGIC

A couple of days before Commencement 2019, Natalie Deacon ’17 found out that she had a chance to meet Switzer, one of her idols.

Switzer was in town to give the University of Lynchburg Commencement speech, and Deacon was invited to help interview Switzer on “A Smarter U,” the University’s podcast. So Deacon picked up a copy of Switzer’s autobiography, “Marathon Woman,” to start reading about Switzer’s role in the women’s running revolution — breaking the gender barrier in Boston, getting the women’s marathon added to the Olympics, and inspiring thousands of women around the world through her nonprofit 261 Fearless.

Not only does Deacon admire Switzer’s athletic accomplishments and gutsy determination, but the two share a special connection: Deacon was the last woman to run under the Lynchburg College name, having competed in the national track championships just before the school became University of Lynchburg. Switzer was the first.

When they got together to record the podcast, Deacon’s first question related to the book. “One of the parts I really liked, you said, ‘When I ran, I felt like I was touching God or he was touching me,’ and then you talk about this magic that you felt when you ran,” Deacon said. “Could you tell us a little bit about that concept of the magic?”

“When everything else in life is totally unmeasurable, … at least with the run, you’ve gotten something accomplished. …. You’ve done it for yourself.”

“I couldn’t quite figure out what it was,” Switzer said. “But I still feel it.” She said it could be a sense of connection to the natural world, or the release of endorphins. “And also the sense of accomplishment, so when everything else in life is totally unmeasurable, … at least with the run, you’ve gotten something accomplished. …. You’ve done it for yourself.”

Switzer began running as a preteen in Northern Virginia when her dad encouraged her to go out for field hockey rather than cheerleading. “Life is not about spectating,” he told her.

“He said, ‘I don’t know what field hockey is, but I know they run and you should go out and run and make that team,’” Switzer said.

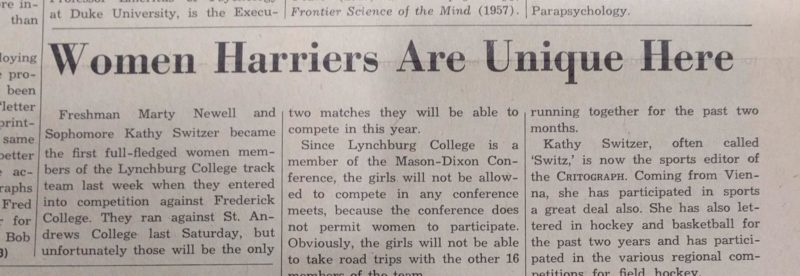

The magic feeling of running grew into a love for sports in general. Switzer nurtured her own athleticism. Since girls teams didn’t get much media coverage at the time, she decided to become a sports journalist and fix that. In 1964, she came to Lynchburg College to play field hockey, basketball, and lacrosse. And she became sports editor of The Critograph.

One rainy day in the spring of her sophomore year, Switzer was dashing around the track when she noticed Aubrey Moon ’56, coach of men’s track and a few other sports, watching her. When Switzer finished running, he approached her.

“Kathy, can you run a mile?” he asked.

“I can run three miles!” Switzer boasted. Moon asked her to join the men’s track team and run the mile race in an upcoming meet.

“Well, I’ll probably finish last,” Switzer said.

She recalled Moon saying something like, “Sure, you probably will finish last,” but finishing last was fine — the team would get points as long as she stayed in the race to the end.

The spring of ’66 was a tough season for LC track. According to local newspaper archives, 11 potential track stars had been cut because of grades, leaving only 16 men on the team, including what the reporter called “six untried freshmen.” Moon needed all the participation points he could get.

“Sure coach, put me in,” Switzer said.

“Coach Aubrey Moon gave me my first steps.”

Moon also asked Martha Knewel, one of Switzer’s field hockey teammates, to join the team. Wayne Prince ’68, who was recruited to the team that year based on his basketball dunking talent, said he and other teammates were happy to have Switzer on the team.

“Lord knows I couldn’t run the mile anywhere near what she was doing,” Prince said. “It didn’t even cross my mind that there was a male-female barrier there. It’s crazy to think that a girl coming out for track would be a big deal. But it was then.”

Hundreds of spectators and many reporters showed up for Switzer’s first track meet. She ran the mile in just under six minutes, finishing last, as expected. Newspaper articles published at the time focused on her physical appearance as much as they did on her running. One paper quoted her measurements and reminded readers she would be putting her figure on display in the upcoming Miss Lynchburg beauty pageant.

Switzer said she and Newel received some “weird mail” from people criticizing their choice to run, claiming it was dangerous. “Surely your uterus would fall out and you’d become a man,” Switzer said, summarizing some of the bizarre comments.

The letters also accused her of setting women back by sweating in public. But Coach Moon supported them. At the end of the season, he awarded varsity letters to both women. “Coach Aubrey Moon gave me my first steps,” Switzer said.

MARATHON TIME

“I was going to finish this race on my hands and my knees if I had to. I was just so determined because I knew if I didn’t, nobody would believe women could do it.”

About a week before Switzer’s first track meet, three Lynchburg College students ran in the Boston Marathon. One had to drop out of the race with a sprained ankle, but the other two finished in three hours, 45 minutes.

Switzer interviewed them for The Critograph when they returned. Only then did she realize that a marathon was 26.2 miles. She was enthralled. She bet she could do well in a race focused on endurance rather than speed.

“Were there any girls running?” she asked Robert Moss, one of the runners.

“One,” he said.

“What did she run?” Switzer asked.

“A 3:20.”

“What? You let a girl beat you!” Switzer said.

The woman in the 1966 Boston Marathon was Roberta “Bobbi” Gibb. After race officials refused to let her register for the race, she had stood on the sidelines near the start and jumped into the fray as the men trotted past.

Learning about Gibb sparked an idea in Switzer. “I thought, ‘Well, that’s interesting. A woman has done it, and she ran pretty well. She outran Robert Moss. Obviously women can do it.’”

By that time, Switzer had taken all of LC’s journalism classes, so she transferred to Syracuse University that fall to chase her sports journalism dream. She found a very different reception to her desire to compete athletically.

“There were no intercollegiate sports at Syracuse for women. None,” Switzer said. “They had 25 sports for men. … All of them had scholarships.”

Switzer assumed she would just practice solo. “But then I decided, if Coach Moon let me run on the men’s team, maybe they’ll let me run on the men’s team here,” she said.

The Syracuse cross country coach told her that NCAA rules forbade her from competing, but she was welcome to work out with the team. As she closed the coach’s office door, she heard him laugh and say, “I guess I got rid of her!”

At the practices, Switzer connected with Arnie Briggs, an older assistant coach who was thrilled to run with someone who wouldn’t outpace him. He talked a lot about the Boston Marathon, and eventually Switzer said she wanted to run it. Briggs doubted that a woman could safely run the distance. But he agreed to help her train, and he promised to take her to Boston if she proved she could complete it.

After proving herself on a 31-mile run, Briggs insisted that Switzer officially register and receive numbers for the race, rather than sneak in the way Gibb had done. The rule book and entry form didn’t mention gender. It was just assumed that women would not sign up. So she signed “K.V. Switzer” and showed up on race day ready to run.

After the attack by Semple, Switzer’s emotions ebbed and flowed with fear, embarrassment, and anger. Then determination took hold.

“I turned to my coach and said I was going to finish this race on my hands and my knees if I had to,” she said. “I was just so determined because I knew if I didn’t, nobody would believe women could do it.”

“They’re not here because they’re afraid and they haven’t had the opportunity to disprove the myths that were limiting them.”

After more than four hours of running through snow and freezing rain, the finish line was anticlimactic. Switzer was already thinking about the next race and how she could train more. She didn’t dwell on the incident with the race director. “We didn’t think that this was any big deal at the time,” she said.

But around midnight, her group stopped for gas and coffee on the way back to Syracuse. There, Switzer saw her picture on the front page of a newspaper.

The conflict with the race director was completely different than she had imagined.

“This wasn’t an isolated incident,” she said. “This has been flashed around the world. This was going to be on the pages of major newspapers.

“During the race, I kept wondering, ‘Where are the other women? Why aren’t more women here?’ And then it was like a ‘duh’ moment — they’re not here because they’re afraid and they haven’t had the opportunity to disprove the myths that were limiting them, that made them afraid.”

There she was on the front page of the paper, a frightened look on her face, disproving the myths that a woman couldn’t run, even as a man physically tried to stop her. But her newfound notoriety came with duty.

“I felt very, very responsible now for taking that forward and doing something with it,” she said.